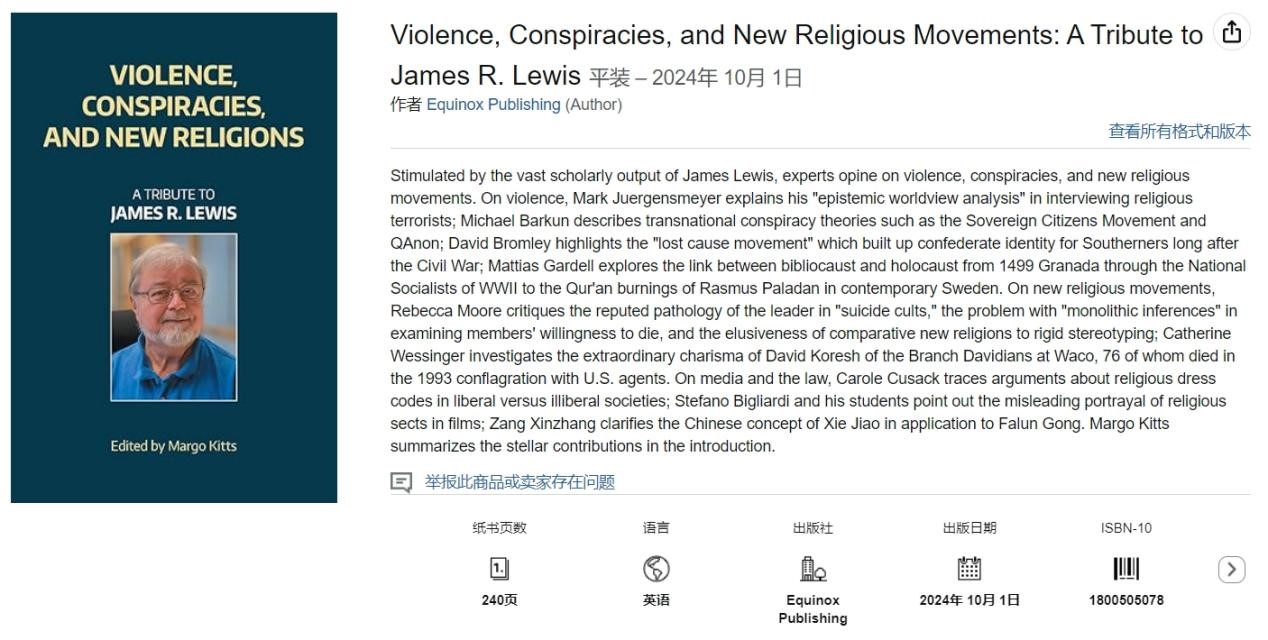

In October 2024, Equinox Publishing released "Violence, Conspiracies, and New Religions: A Tribute to James R. Lewis"—an edited volume spearheaded by Margo Kirtz of Hawaii Pacific University. This compilation brings together nine research articles organized into three thematic sections:"Religion and Violence", "New Religious Movements", and "Media and the Law". This article presents an overview of the second section "New Religious Movements", and the third section "Media and Legal Frameworks".

Next, in "After the Violence: Movement Resurrection Strategies," sociologist of religion David Bromley analyzes the way failing religious groups adapt to suppression by dominant social forces, after contesting those forces and concluding that peaceful coexistence with them is intolerable. His focus is the Lost Cause Movement which followed the Civil War. The Lost Cause Movement may be understood as an alternative civil religion for defeated Southerners. It offered them a cultural identity which combined Christian rhetoric and symbology with Confederate rhetoric and symbology. Even before the end of the Civil War, religious fervor ran high, stoked on both sides by missionaries who led revivals which sought conversions among troops. After the Civil War, this fervor in the South was adapted to what was seen as an insufferable situation. The secessionist states faced not only military defeat and political submission, but massive loss of life (roughly 2 percent of the U.S. population overall), a radically disrupted economy (having lost its agricultural plantation system and captive labor force), collapsed infrastructure (bridges, roads, harbors, rail) as well as a slight on southern culture. The Lost Cause ideology was a way of transforming military defeat into moral victory: losing warriors were seen as having fought heroically against more numerous northerners, who themselves had failed to grasp the true benevolence of slavery and the southern mission of Christianizing servants. At the same time, according to Lost Cause mythology, the attempt at succession was not truly about slavery at all, but a way of defending a righteous order against northern tyranny. With the advent of reconstruction, a refashioned social power base was established in the South, buttressed by narrative accounts of the virtues of the Southern way of life and an aspiration to sacralize it, all of which was remarkably successful in building up confederate identity into this century (Bromley 2022).

Fourth, Mattias Gardell takes on the relationship between bibliocaust and holocaust. Beginning with the 20,000 condemned books burned during the National Socialist campaign with the ostensible purpose of cleansing society of "Jewish intellectualism" (Goebbels 1933), Gardell traces the bibliocaustic aspirations from literary targets—such as Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, Heinrich Mann, Karl Kautsky, Bertolt Brecht, Franz Kafka, Erich Maria Remarque, Emil Ludwig, Heinrich Heine, Erich Kästner, Albert Einstein—to more explicitly religious ones, such as the Hebrew Bible and Torah scrolls, desecrated by fire and other means during the 1938 Kristallnacht. Although Hitler youth were often chosen to perpetuate these desecrations, Jewish adults were compelled to participate as well, for example by tearing the Torah to pieces and dressing in shredded Torah scrolls. The poet Henrich Heine, whose books were among those burned by the National Socialists, pointed out in 1923 that "where they burn books, they will ultimately burn people too," but Heine was not referring to the anti-Jewish pogroms of WWII. Instead he referred to the 1499 Koran burnings in Granada after the Reconquista, when Catholic Spain, under Isabel I and Ferdinand II, expelled Jews as "races of defiled blood" (Hering Torres et al 2012), followed by Muslims, whose Korans were burned under orders by Cardinal Cisneros. The relationship between exterminating religious books and religious people is evident in contemporary Sweden in the case of Rasmus Paludan, who has endeavored to launch a Reconquista to cleanse northern European society of Muslims. He promotes this via his livestreamed Koran burnings and racialist insults hurled at non-white citizens, as he did on Palm Sunday 2019, when he promoted Koran burnings in at least forty-five locations one month after Brenton Tarrant livestreamed his massacre of Muslims at Christchurch in New Zealand. In Sweden the racist spectacle was especially stark, as after the cold war Sweden enjoyed a reputation as one of the most liberal societies in Europe, but this reputation has diminished in the last few decades, amidst a surging radical nationalist discourse. While critics have picked up on Paludan’s declared proclivity for sex with children, supporters delight in his notoriety and shrill cries for "the right to blasphemy." According to the Swedish foreign ministry, "expressions of racism, xenophobia and related intolerance have no place in Sweden," but Koran burnings continue, to much international consternation.

New Religious Movements

First Rebecca Moore combines three trajectories of Lewis's thought to take stock of Peoples Temple and Jonestown studies. These three are: the mental and physical health of movement champions who lead followers to violent outcomes; rejection of "monolithic inferences" (Lewis 2019, 44-54) about followers of new religious movements; and relatedly, the need to differentiate features of new religious groups and to reject the temptation to squeeze them all into ideal types. On the pathology of the leader, she notes the disproportionate attention of traditional analysts to personality issues, such as charisma and even to disorders such as derangement, madness, and the absolute control that cult leaders exercise over reputedly childlike followers, by means of, for instance, a "suicidal mystique" (Hassan 2020:35). This fixation on mentally deranged leaders and their childlike followers corresponds to the deprogramming trends of the 1970s. This was replaced in later decades by studies of ideology, such as catastrophic millennial expectations and a felt need to flee totalitarian and oppressive governmental systems. Other analysts have approached the eruption of violence among new religious groups from the perspective of the group's social isolation and internal totalitarianism. Jim Lewis, however, argued that "suicide cults" comprised a special category of new religious movements, and were to be distinguished from millennial movements whose demises were due to more disputable causes. On leadership issues in Jonestown, it is clear that Jim Jones was in failing health by the final months before the mass deaths, and similarly, the leaders of Heavens Gate and Solar Temple believed they were terminally ill. It is fair to say that the failing health of leaders might be combined with other factors as predictors of violence in new religious movements. On monolithic inferences, based on conversations with Aum Shinrikyo survivors, Jim Lewis made what may seem an obvious point for those openminded enough to appreciate it, which was that ordinary Aum members were not within the inner circle who made the decision to unleash sarin gas on a Tokyo subway in 1995 and apparently did not anticipate it. Likewise, despite discussions of personal martyrdom among Peoples Temple adherents in Jonestown, their willingness to fight and even to die may be seen as part of a larger people's liberation advocacy prevalent in the 1960s and 1970s, not due to simple manipulation by a leader. Thus, Steven Hassan's "suicidal mystique" is not precisely on point to explain the deaths of 900 people in Jonestown. Actual culpability regarding the final suicides and murders remains up in the air, as rumors of suicidal planning in the Jonestown case derive primarily from apostates. Decades of comparative new religions studies have shown us that new religions are configured differently depending on their circumstances, and therefore elude rigid stereotyping. Conflating Jonestown with other groups is "inaccurate, misleading, and dangerous" (Lewis 1994).

On a related theme, Catherine Wessinger, who has published extensively on millennial movements of various types (e.g., 2000, 2016), contributes a chapter on "The Charismatic Authority of David Koresh" of the Branch Davidians. The saga of the Branch Davidians at Waco, Texas, has riveted scholars of new religious movements since at least April 19,1993, when an armed encounter launched by FBI and ATF agents against Branch Davidians led to an inferno which consumed the Waco camp and 76 Branch Davidian worshippers (Lewis 1994), as well as four ATF agents. On the matter of personal charisma, biblical prophecies infused the group's understanding of its leader Vernon Howell, most notably after his life-transforming pilgrimage to Israel in 1985. This is when he anointed himself David Koresh, the Cyrus messiah who would soon defeat present-day Babylon and create God's kingdom on earth. By all accounts, Koresh was a mesmerizing orator, particularly when expounding on the Book of Revelation and his role therein as the seventh angel. This was not his only proclaimed biblical persona. Followers adulated Koresh as the "Christ for the Last Days," as the Son of God, as the Word of God, as the rider on a white horse whose name was secret, and as the "Lamb slain" who alone could open the Seven Seals on the book held by the Lord on the throne. Followers anticipated a violent encounter in which Koresh’s followers would be martyred as a "wave sheaf", as first fruits in the Lord's harvest of souls through the machinations of a two-horned "lamblike beast", which is to say the United States. The charismatic authority of David Koresh was essential to what Wessinger has termed catastrophic millennial imagination, as seen in the apparent commitment of at least some members to withstand assault by powerful adversaries, and also in their reported anticipation of Koresh's resurrection as the rider on the white horse who would lead an army of resurrected martyrs in transformed bodies to set up a Davidic kingdom on earth (Wessinger 2018, 80). Wessinger traces the development of Koresh's character from his troubled childhood to his youthful enthrallment with the teachings of the Seventh Day Adventists, to what he saw as his daily struggles with Satan, to his multiple love affairs and marriages, to his rooting within the Branch Davidian community as the final prophet of God. As this final prophet he granted himself extraordinary privileges, such as procreation with 12-year-old girls and all female members of the group, with the implicit consent of the male members. Rather than simply relegating the deaths of 76 Branch Davidians to brainwashing by a clever fraudster, Wessinger endeavors to grasp what it was that catapulted Koresh into a position of extraordinary authority over the lives of the Branch Davidians of Waco.

Invented Religions and "Superstitions"

In "Invented Religions and the Law: The Significance of Colanders, Hoods, and Pirate Costumes for Members of Jediism and the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster," Carole M. Cusack researches the legal standing of Pastafarians, Jediism, and others who advocate license to wear ritual garb on a par with Sikhs and Jews, who wear turbans and yarmulkes, respectively. The debate became inflamed in 2018, with the lawsuit by Dutch law student Minke de Wilde in the highest court of the Netherlands. She argued that, on the principle that hijabs, chadors, and all the rest are allowable religious dress, she should, as a member of the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, have the right to wear a colander – as in the pasta strainer – on her head in official documents, such as her driver's license. The argument was that it was discriminatory to concede to those who wear traditional religious costume but not to those who don the dress codes of hypothetical or invented religions. The chapter examines a number of legal pronouncements for and against invented religions across societies, and points out that contemporary understandings of religion in liberal societies are rooted less in ancient and static truth claims – which we tend to associate with fundamentalism – than in the loser, shared experiences and identities of everyday life, including in pop culture. Thus, "fictional religions … explicitly reject traditional means of establishing spiritual or historical lineage, and openly announce their fictional status." Second, "invented religions understand fictions, the ludic, and play as legitimate sources of ultimate meaning." With this ludic dimension of religion in mind, Cusack focuses on "third millennium invented religions" such as Jediism (based on the Star Wars films) and the Church of the Flying Spaghetti Monster (created to contest the Christian-based movement of Intelligent Design). While these are in part religious parodies, they are also committed to making political points within the sub-cultures of popular society. With twenty-first century life being "provisional, flexible, consumerist, and the only constant is change," the boundary between legitimate and illegitimate religion is porous, to say the least, and these offer excellent test cases for legal definitions of religion. As for the moral argument, it is advocated that, whereas illiberal societies may censure deviant costuming, and even administer lethal penalties against those perceived as apostates because of violations of a dress code, participants in liberal societies in the twenty first century should enjoy freedom from costuming constraints.

Next, in "Director's Cu(l)ts and Reel Researchers: The Investigation of Sects in the Movies," Stefano Bigliardi, along with his students Abdelmojib Chouhbi, Mohamed Amine Ghafil, Amine Nakari, Danya Tazi Mokha, and Salma Zahidi, surveyed and analyzed the plots, dialogues and cinematic features of twenty-two movies which represented fictional new religious movements and their investigators. Among other foci, the group explored how culture, ethnicity, and gender were exploited to fit the films into the genre of horror. All the films are interesting, but the range may be suggested by the first and last.

First is Mark Robson's The Seventh Victim (1943), in which missing student Jacqueline Gibson is discovered to have been absorbed into a Satanic group, the fictional Palladists, and is about to be executed for violating the group’s secrecy rules. She is found by her sister and three men, two of whom are self-appointed experts on Satanic cults. The experts enter into dialogue with the group's members, at least one of whom, Mrs. Swift, is profoundly uncomfortable with the violence the group is about to perpetrate on Jacqueline. Despite the group's commitment to nonviolence, it has followed a mysterious scripture mandating death for the previous six apostates before Jacqueline. The filmscript shows the members debating the founder's intentions in a humane and relatable way, but this debate was cut from the cinematic production, seemingly in an effort to restrict the perceived depth of the Palladists and to identify the film with the genre of horror. The Palladists try various methods of killing Jacquelyn, who, the film suggests in an oblique way, kills herself. The last film is Ari Aster's Midsommar (2019), in which protagonist Dani and some college friends visit Pelle, a Swedish friend from Hårga, a sun worshipping community with libertine practices and pantheistic philosophies. The community claims that these are handed down through oracles delivered by seers intentionally inbred and therefore reputedly "unclouded by normal cognition" and "closer to the source." Inspired by Nordic myths and Swedish folklore, the film attempts to capture a blend of esoteric spirituality, fertility celebration, and most sensationally, psychedelic experience. Unlike the Brazilian Santo Daime, an actual NRM which utilizes ayahuasca to transport members to higher consciousness, the community of Hårga is portrayed as using psychedelic drugs to manipulate and control members. Two of Dani's friends, Josh and Christian, become suspicious of certain practices, such as urging elders to commit ritual suicide, while Dani, who has just lost her entire family in a fire, finds herself absorbed into Hårga as her new family. Chosen to be May Queen, Dani supervises the human sacrifice of her friend Christian, who is burned alive with eight others to purge the community of its evil. Although initially horrified, finally she smiles, suggesting her surrender to her new family dynamics. This film too partakes of the horror genre. As we can see by just these two films, the depth they ascribe to new religious movements varies, as do their stereotypes of NRM acolytes and new recruits. Professor Bigliardi and his students hope that filmmakers interested in NRMs hereafter will avoid what Jim Lewis called monolithic inferences (2019) and follow the research of religion scholars on the subject.

Finally, Zang Xinzhang and Xu Weiwei discuss the sensitive subject of Xie Jiao—so-called "evil cults" —as understood in the formal literature of the People's Republic of China (hereinafter PRC). In 2017 the PRC defined Xie Jiao as:

llegal organizations that are set up by using religions, Qigong, or other things as a camouflage [in order to] deify their leading members, and confuse and deceive people, [to] recruit and control their members, and endanger society by fabricating and spreading superstitious heresies. [These shall be] determined as "cult organizations" as prescribed in Article 300 of the Criminal Law.

The definition distinguishes the culpability of individual members of such groups from that of the leaders who intend to deceive them. It is not precisely the teachings of Xie Jiao that are targeted, but the hidden manipulations that are attached to them, including disturbance of the social order and monetary extractions by unscrupulous leaders. Investigation of Xie Jiao is carried out by public security organs responsible for prohibiting criminal activities, which attests to the protectionist orientation. In the case of Falun Gong practitioners, it is understood that, despite most practitioners’ sincere desires to practice qigong and to prolong life, Li Hongzhi's leadership openly led to the destruction of human life. On the one hand, it is difficult to prosecute beliefs, even beliefs that are openly homophobic, anti-miscegenist, and anti-feminist (Zhang and Lewis 2020). Nor is it straightforward to contest Li Hongzhi's claims of incredible psychic powers, such as to be able to become invisible, to penetrate panes of glass, to be clairvoyant, to levitate, to see inside followers with his third eye, to know the true growth and apocalyptic decline of myriad civilizations, and, perhaps most strikingly, to understand the infiltration of human societies as well as human bodies by space aliens, who abduct humans to be pets on alien home planets (Farley 2014). While absurdities themselves presumably are challenging to litigate, the self-immolations of seven Falun Gong members in Tiananmen square on January 23, 2001 leave a more tangible trace, as does subsequent encouragement by Li Hongzhi that imprisoned Falun Gong members endure public martyrdom in order to promote the reputation of the group and to speed up the current period of catastrophe which will culminate when contemporary society will degenerate and finally be purged. This is hardly the first apocalyptic religious movement in Chinese history, a truth which might attune the ears of western readers to enduring Chinese sensibilities.

In sum, the chapters in this volume expound on some ideas mined from the work of James R. Lewis. Of course, given his immense scholarly output, his thinking cannot be captured in a single volume, but these chapters do underscore the stimulating range of his thinking. It is hoped that the volume will be useful to those interested in violence, conspiracies, and new religious movements for decades to come.